Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants

by Douglas W. Tallamy

(An earlier version is titled Bringing Nature Home: How Native Plants Sustain Wildlife in our Gardens)

I read this book after a review of it on the Washington Native Plant Society listserve by Allyn Weaks. This review is partly his and partly mine. My first thought about writing this review was how to convince gardeners to purposely grow plants that would attract insects that eat them! I decided it was worth a try if it meant that the insect damage to the plants would be minimal since the insects would attract the birds that Audubon folks love!

The first part of the book explains why we need bugs and bug diversity, why only native plants have a hope of producing that, and why alien plants, and the nursery trade that pushes aliens so hard, are actively harmful – loss of bug (bird/animal) habitat as well as invasive diseases and pests they introduce. The author cites many studies and references: 96% of North American birds feed insects to their babies. A native plants will support 10-50 times more insect species than an exotic. A prairie invaded by an exotic grass has only half as many mockingbirds as a nearby intact prairie.

Only 3-4% of U.S. land is genuinely undisturbed. While this statistic is depressing, it can be ammunition for convincing ourselves and our lawmakers to fight the huge lawn and nursery lobbies that create these problems, including the work and resources it takes to remove invasives from public and private lands.

On a happier note, a large part of the book is devoted to specifics of how anyone with even a small plot of land can help reweave the web – restoring the sun-plant-insect-bird/animal links – by planting native plants. While Tallamy’s references and studies are largely east coast (That’s where the majority of this kind of study has been done.), he includes regional plant suggestions, although neglecting bitter cherry, cascara and black hawthorn under Pacific Northwest. A table of genus of plant versus number of butterfly species that eat it is included. Examples: oaks (534), willows (456), hawthorn (159), maple (285).

There is a description of each tree genus and an illustrated catalog of the major groups of herbivorous insects (much less about predator insects and other arthropods).

He uses Lepidoptera (butterflies) as a stand-in for all insects, partly because they are the best studied, partly because they are a large fraction of the insect biomass and species diversity and partly because, if there are butterflies, there will also be other bugs. He includes many good photos, especially of butterflies on natives.

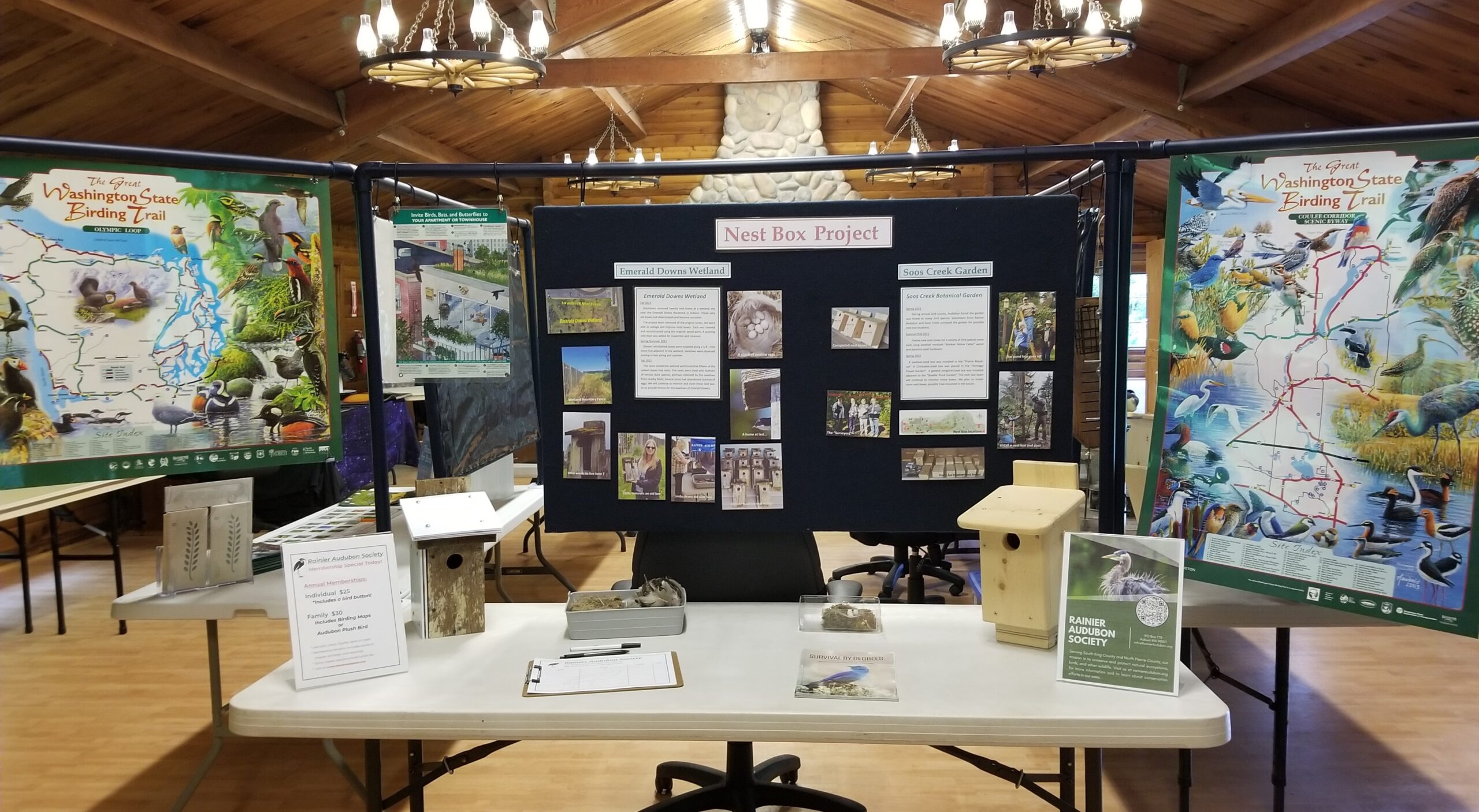

Overall, the book is an easy, informative read and a not-so-subtle plea to help stop the loss of habitat for the birds and animals we love (and need for the health of our planet) by buying and growing native plants. Several Rainier Audubon members are becoming experts on native plants and can give helpful information to anyone interested. Also, our website has a link to the Washington Native Plant Society for expert information.