Mewsings from Millie – December 2024

(Reprinted with permission from the Burien Wild Birds Unlimited store.)

BRRRRRR! Hello again and welcome to my musings!

Do you know the story of why we have winter? Demeter, the goddess of agriculture, had a daughter, Persephone. One day Hades, the god of the underworld, snatched Persephone and carried her down to his dark, dreary universe. Persephone could not be found for some time. Then one day Apollo spotted her there and reported his find to Zeus. Zeus sent Hermes, the messenger, to bring Persephone back. Unfortunately, Hades had given Persephone six pomegranate seeds to eat, and she was then bound to return to the underworld for six months every year. When Persephone returns from the underworld, Demeter makes the earth bloom and grow. When her daughter returns to the underworld, Demeter stops the growth and we experience winter.

A few people who come into the store ask if Robins stay all year or fly south for the winter months. One of my people knows from personal experience helping with the Christmas Bird Count that if there is sufficient food on the breeding grounds, Robins will remain where they spent the summer. Literally hundreds of Robins have been seen on farmers’ fields during the winter months.

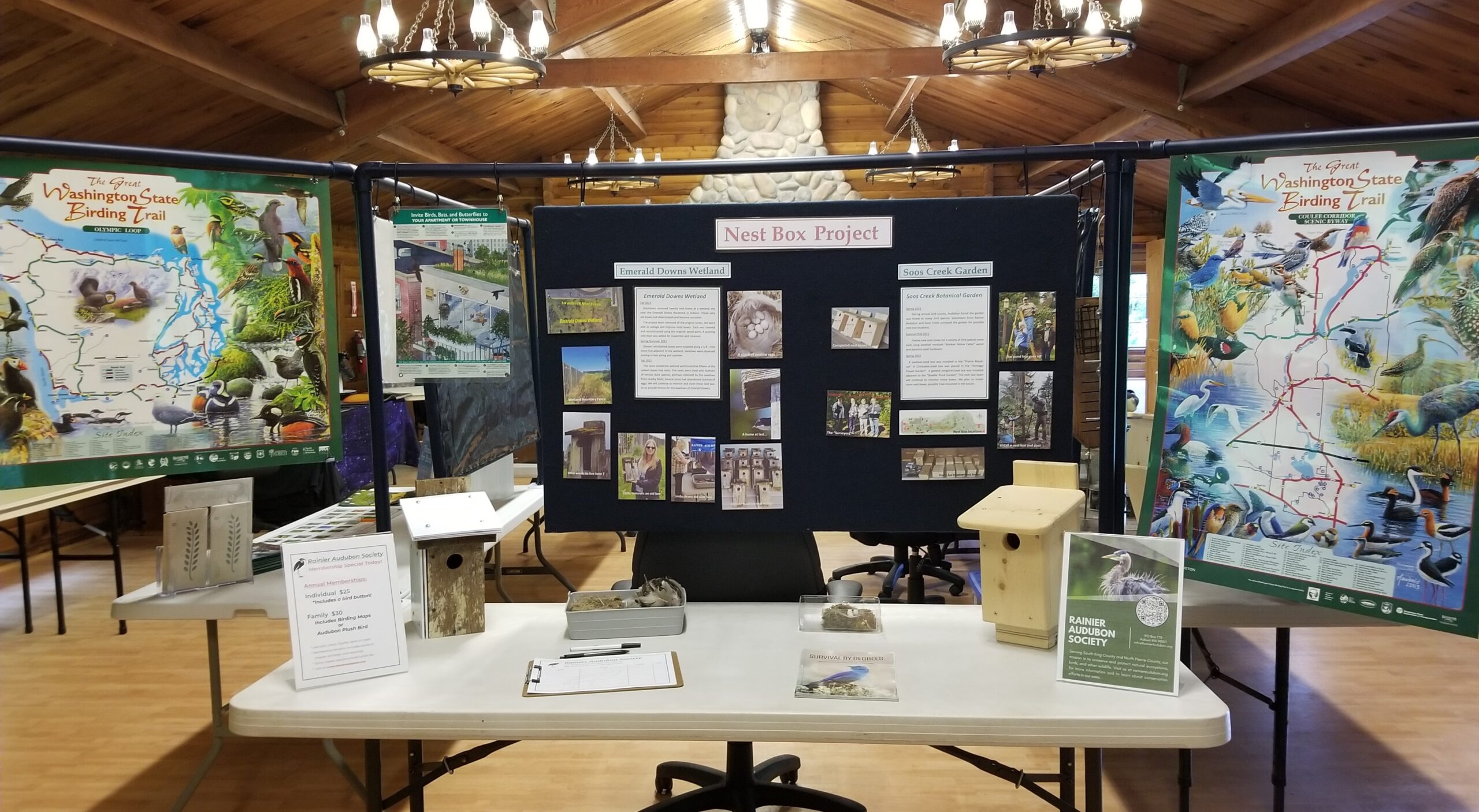

If you have birdhouses in your yard there is no need to take them down for the winter. On very cold nights, some birds will use the houses for shelter and roosting.

Winter is the time of year when people like to plan a day trip to the beautiful Skagit Valley to observe Snow Geese, Tundra Swans, Trumpeter Swans and other winter visitors from the north. But how can you tell them apart? Here are a few tips:

Snow Geese stand about two feet tall with a wingspan of fifty-four inches. They’re white with black wingtips, pinkish legs, and a pink bill with a black ‘grinning patch’. Snow Geese forage mostly on land, making harvested agricultural fields a critical part of their winter habitat. They will forage in shallow water and estuaries. These geese feed almost entirely on grasses, shoots and waste grain. Snow Geese are often called ‘wavies’ due to the irregular waves they form in flight.

The much larger Tundra Swan, at one time commonly seen in the Skagit, can be over four feet tall with a wingspan of sixty-six inches. They are white with black bills as adults that taper to a thin horizontal line at the eye. There is usually a patch of yellow skin below the eye, though this may be absent.

The even larger Trumpeter Swan measures five feet tall with an eighty inch wingspan. They are also white with a long, black bill that extends to the eye in a broad triangle.

Both of these swans have black legs and feet. They forage on land and in water for plants, waste grain and potatoes. I’m happy to say that after almost becoming extinct a century ago, the Trumpeter Swan is making a rapid comeback.

On the topic of these visitors to the Skagit Valley, here are a few collective nouns to describe groups of geese and swans: a skein or plump (on water) of geese, and a whiteness or bevy of swans.

Until next time,

Millie, the Muse of Mews